Google Wave: The Tenet of Productivity Apps That Failed

Google’s attempt to merge email, chat, documents, bots, and real-time collaboration into one living, shape-shifting workspace—years before the world was ready. In 2009, it delivered features that feel normal today: live cursors, instant edits, shared documents, embedded apps, and cross-server collaboration. Under the hood, Wave ran on a futuristic architecture of micro-updates, versioned event logs, optimistic merging, and multi-domain syncing at a time when real-time web barely existed. It was a Bruce Wayne in a moneyless world.

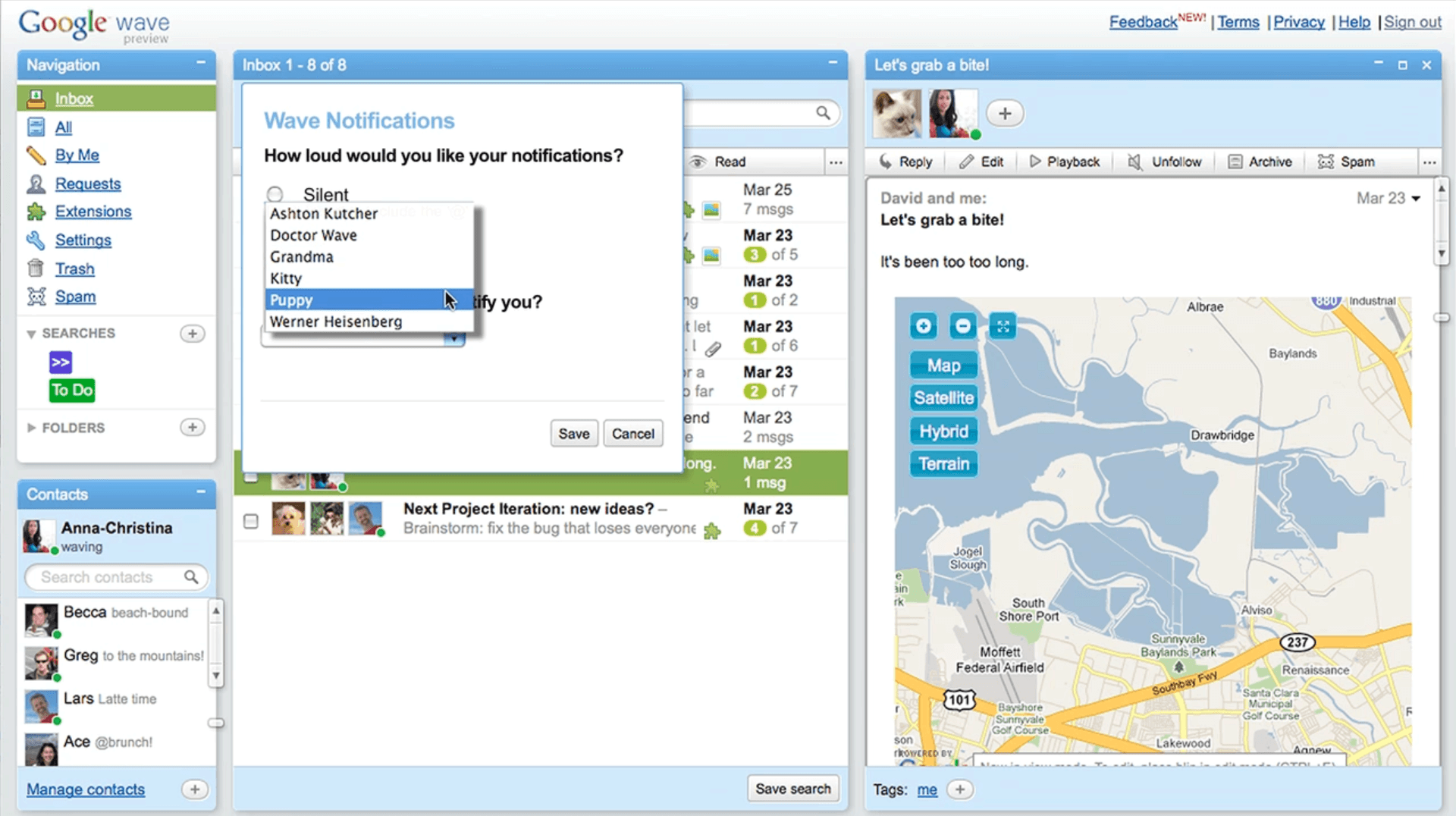

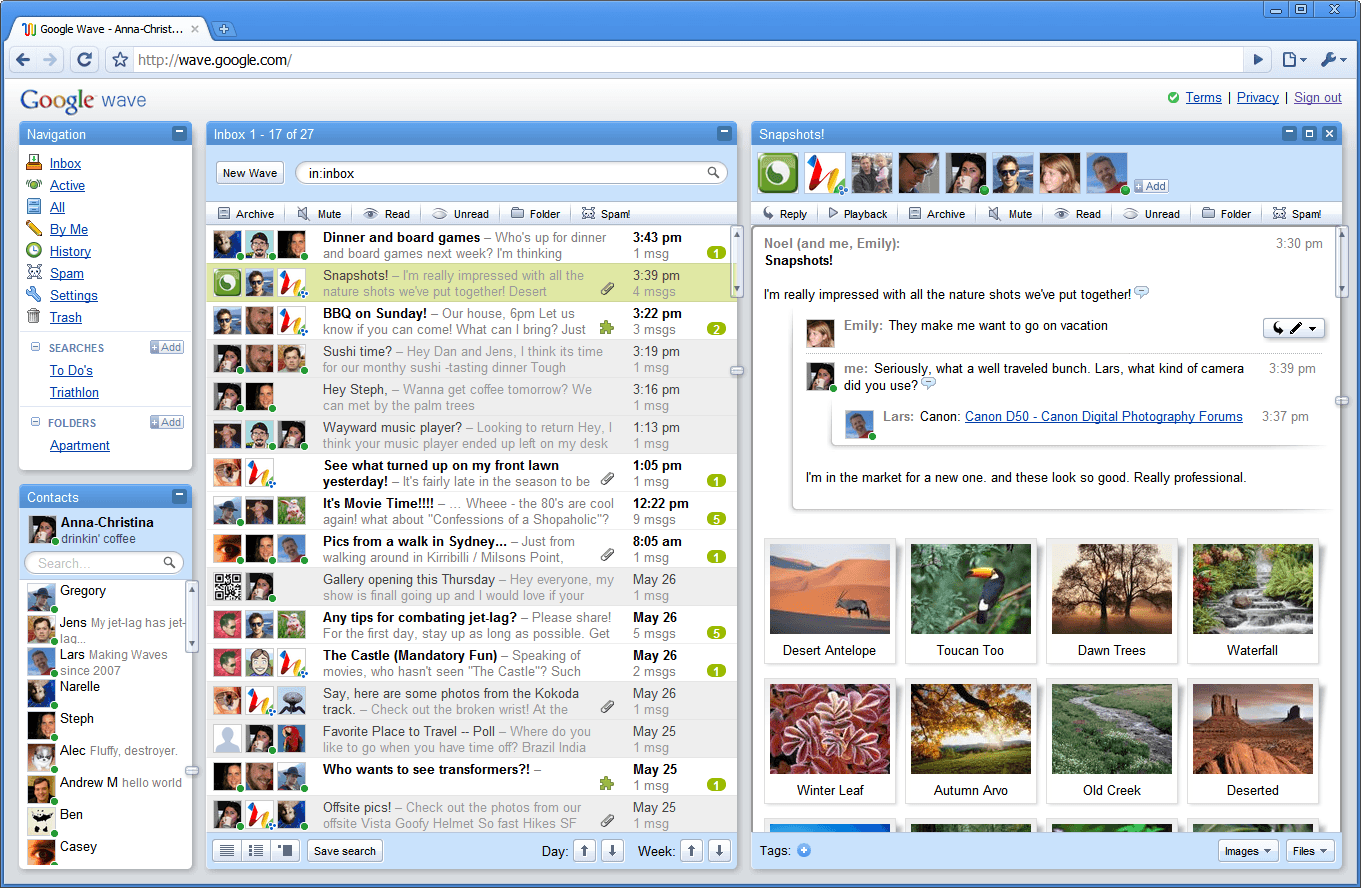

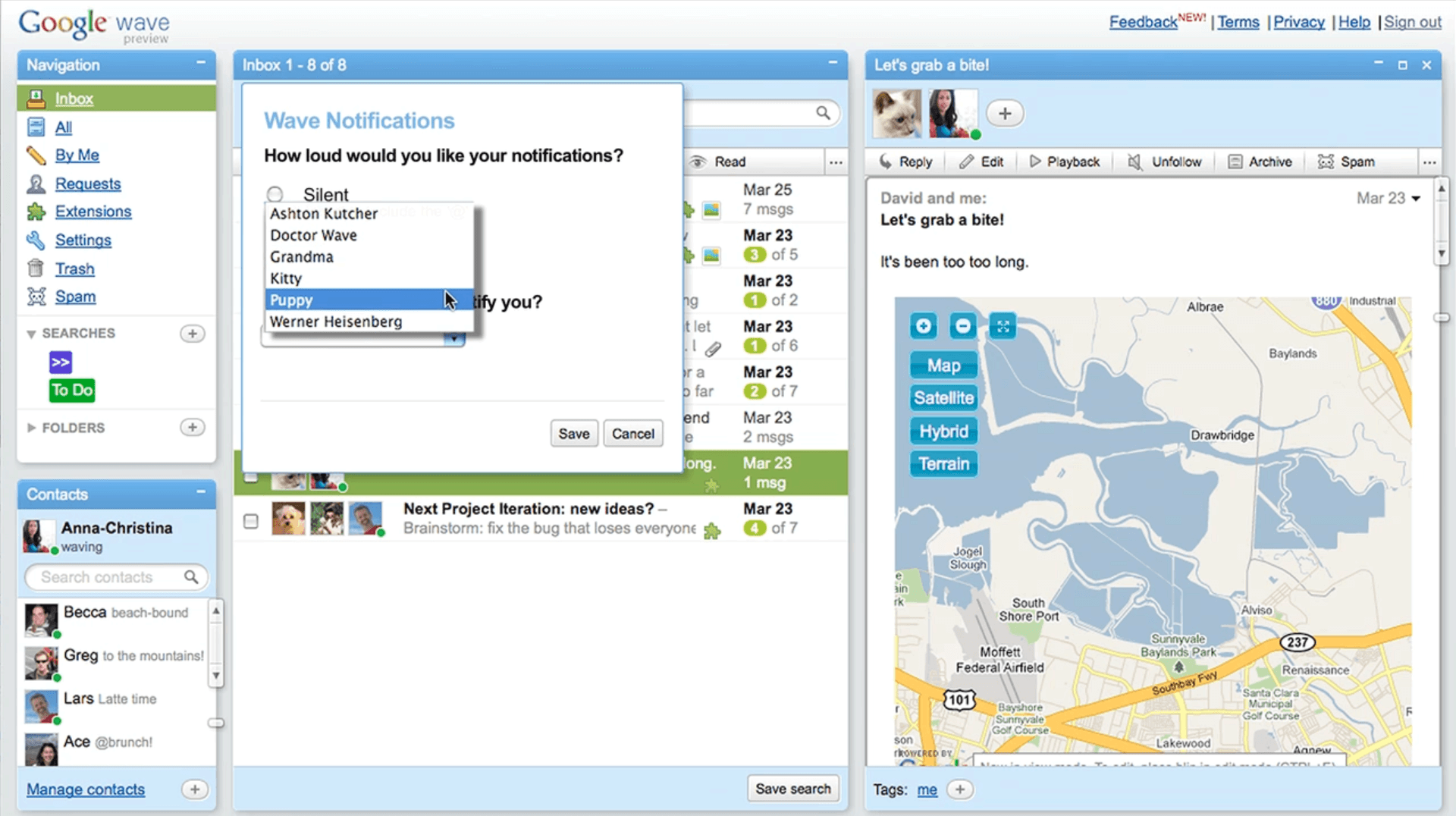

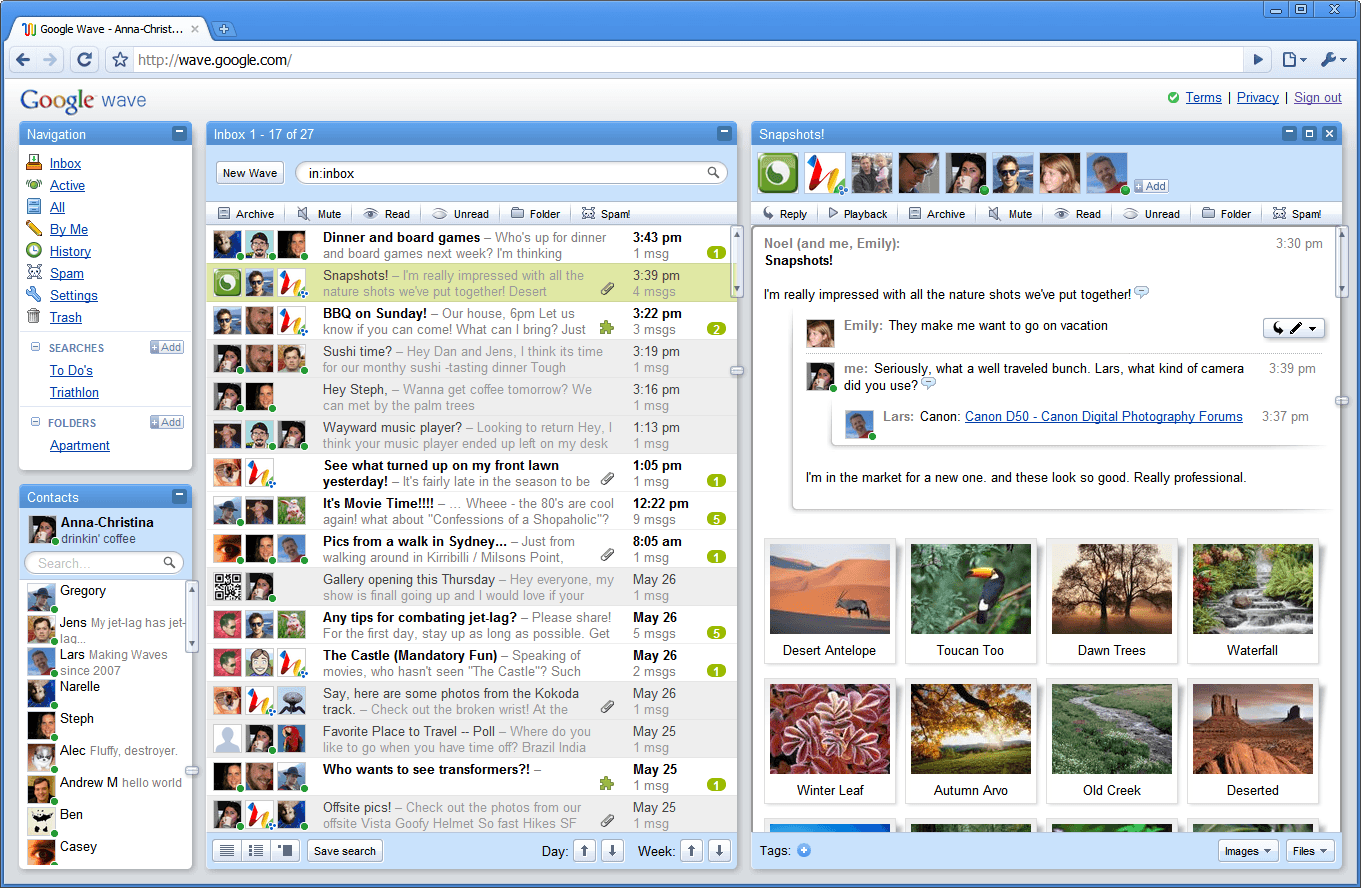

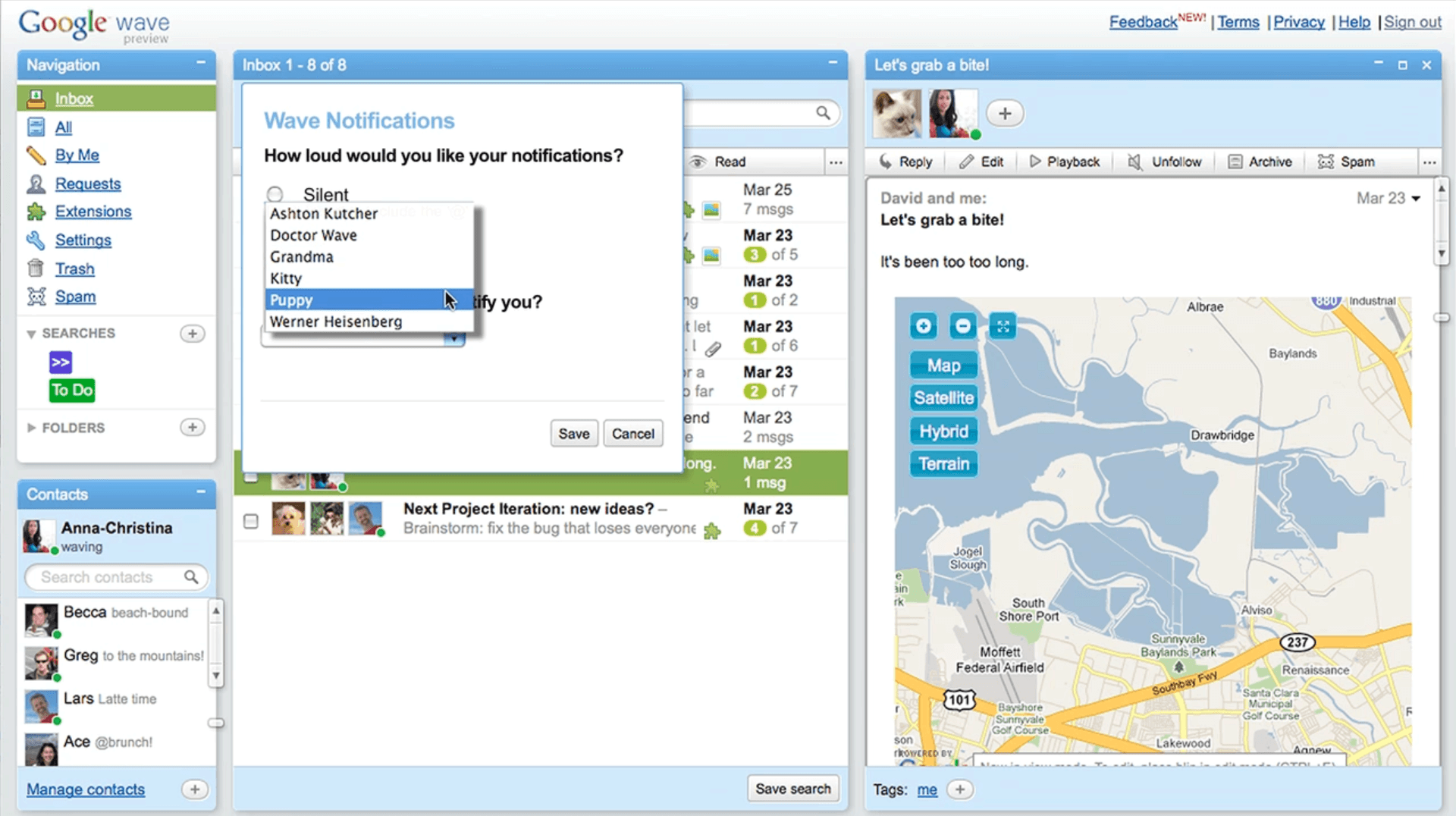

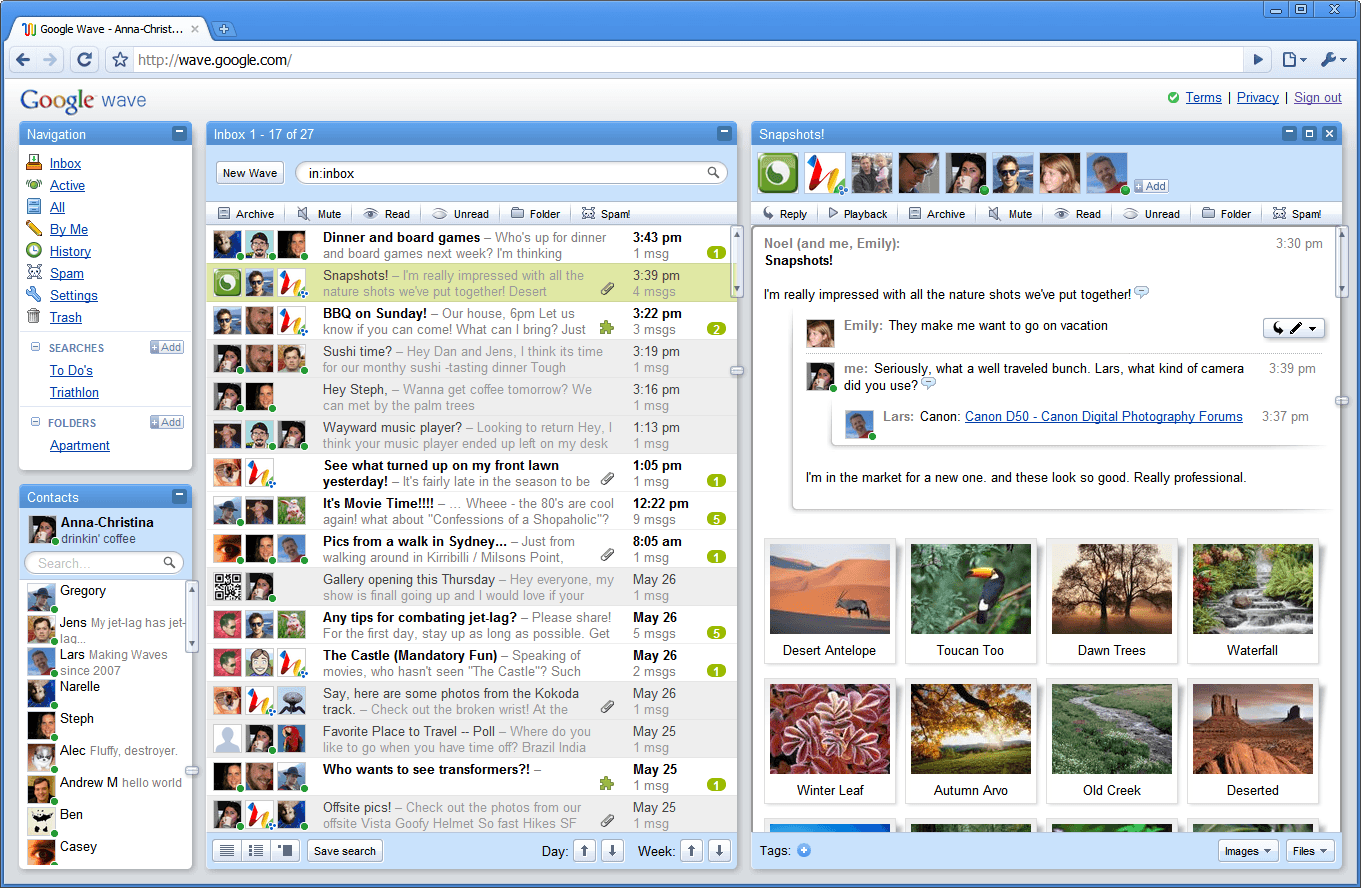

Imagine opening one window that replaces your inbox, your chat, your shared documents, your project channels, and even your little side apps like polls or maps. Imagine typing a word and everyone watching it appear letter by letter. Imagine dragging a file into a conversation and the file instantly becoming part of the shared document. Imagine replying inside someone’s paragraph as if the entire conversation were clay you could reshape at any moment. All of this happening in real time across browsers, devices, servers, continents back in 2009.

That fever dream was Google Wave.

Long before Notion, Slack or any collaborative tools existed, Wave was out there to solve a problem that was way ahead of its time. Every conversation was a document of its own and every document was a space where humans and bots could collaborate in real time. Wave treated messaging as a constantly evolving chain of inferences. Work happened inside a conversation instead of around it. The architecture backed this vision with serious engineering muscle: real-time merging, multi-server federation, event-stream persistence, client-side optimistic updates, and a universal representation for everything from text to files to bots. It was ambitious, it was bold, and it was genuinely ahead of its time. But ambition had a price and Wave paid all of it all at once.

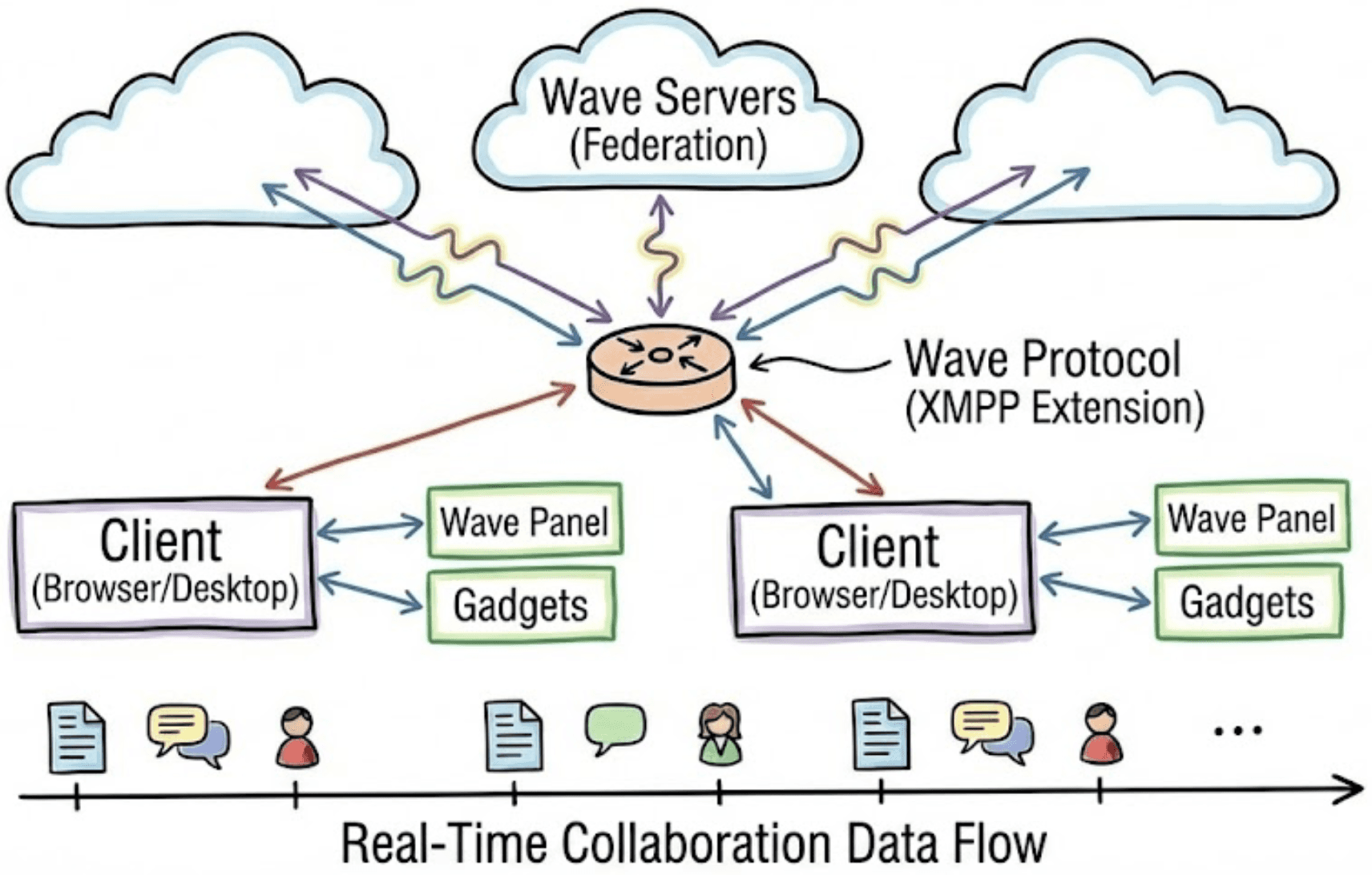

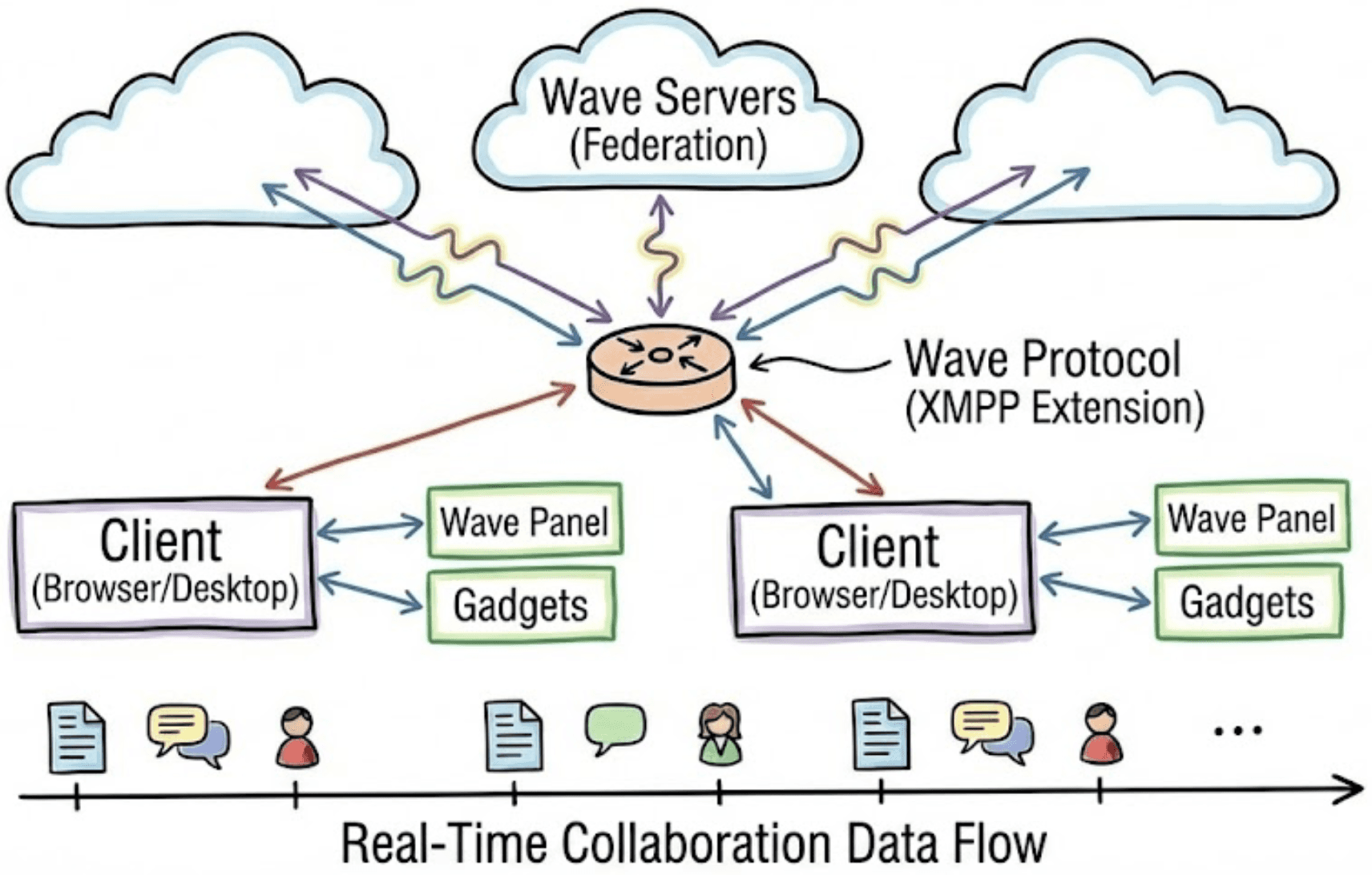

The Master Architecture

When you typed even a single letter, your browser didn’t upload a paragraph or send a diff. Instead, it sent a tiny instruction like: Insert ‘a’ at position 142, based on version 389.

If someone else typed in the same region before you, the server adjusted the position. It updated its authoritative version. It appended the event to the log. And then it broadcast the smallest possible update to everyone else. Today if you build a collaboration tool your architecture would simply look something like this :

1. Put files on S3

2. Put docs in Postgres/ Firestore

3. Use Redis for updates

4. Stream live changes with WebSockets

5.Scale with serverless

Wave did not have these luxuries. Instead it used Google’s internal distributed systems to store :

1. Snapshots - periodic full versions of the entire wave

2. Event logs - tiny changes being changed forever

Even a file was inserted as a file object pointer. Wave did not have the privilege of throwing in Redis streams / CRDT libraries so it build its own pipeline. Every change was compared to the client version to server version, adjusted according to the edit so that it lands correctly and the master copy is updated. The newer version was incremented and the updates were broadcasted to all connected browsers. This was happening dozens of times per second, in a world where most web apps were still doing full page reloads.

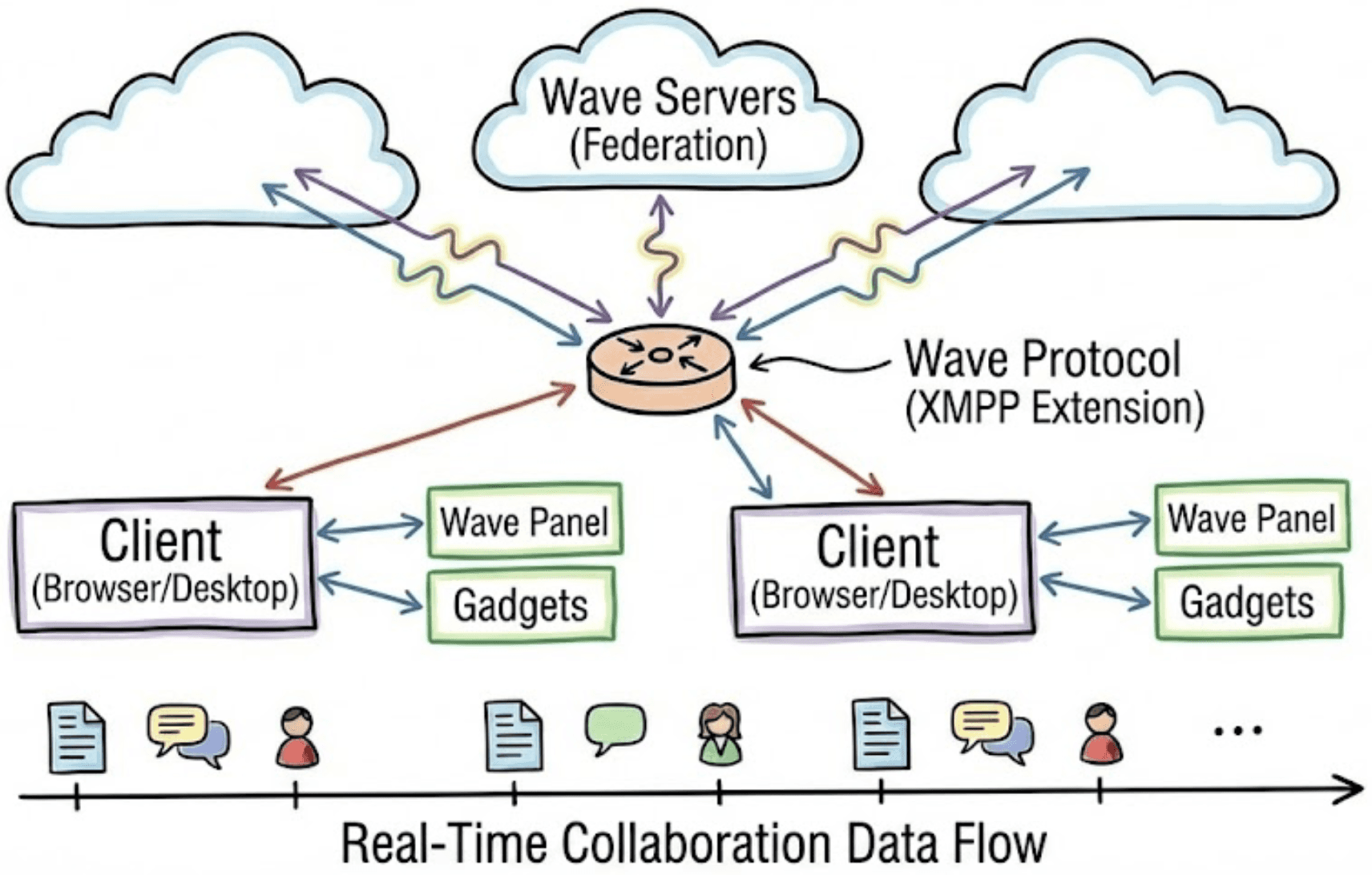

One of Wave’s wildest architectural ideas was that different organizations could host their own servers, yet still participate in the same wave. Imagine if a Slack channel could be shared across two companies without both sides being on Slack’s cloud. Modern tools don’t do this. Wave did. If you added someone from other domain :

1. Your server sent their server the snapshot.

2. All future micro events were forwarded

3. Both servers maintained their own copies, always in sync.

4. Both servers broadcast updates to their own respective users.

Distributed event logs before Kafka, bots before LLMs became a thing, real time editing before Figma was even born - Wave wasn't just early - they were running on an architecture no one had. It was a Formula 1 car if introduced in the 1900s.

One Shot

a live shared document streamed through tiny updates, backed by a versioned event log, merged by an always authoritative server, synchronized across multiple domains, and built before the internet had the infrastructure to support such a thing.

Weak Onboarding and Complexity

Wave repeated Gmail’s invite-only rollout but with completely different stakes. Gmail worked fine under an invite model because users already knew what email was and could use it immediately even with just one contact. Wave, in contrast, was unfamiliar, required a group of people to see value together, and depended on network effects to demonstrate its potential. By limiting invites and spreading them slowly, Google prevented users from onboarding their actual work groups, so people tested Wave with a handful of friends for a few days and quickly abandoned it.

Consumer behavior in 2009 did not align with what Wave required. People were deeply entrenched in email, instant messaging, SMS, and growing social networks. Enterprises had begun adopting SharePoint, internal wikis, and early collaboration platforms. Wave’s benefits were real but subtle, and they did not obviously outweigh the effort required to switch.

Confusion about purpose & value

Wave never answered the simplest product question: what problem does this solve better than the tools people already use.

Some people approached it expecting a better email client, others thought it was a new type of chat, others assumed it was a document editor, while the Wave team’s own messaging often described it as a platform rather than an app. This ambiguity made it nearly impossible for new users to understand why they should adopt it or what everyday habit it was supposed to replace.

Many reviewers called it “too ambitious,” “too complicated,” or simply “too much,” noting that instead of reducing friction, Wave often increased cognitive load by presenting far more information and activity than users could comfortably track. Even experienced early adopters often needed long explanations just to understand how to reply, where edits were happening, or how to control the flow of conversation. When a product requires effort just to understand the basics, mainstream adoption becomes extremely unlikely.

Even though Wave offered robots, gadgets, and the promise of becoming a programmable collaboration platform, the ecosystem never reached meaningful scale. The extensions that existed were mostly prototypes or novelty features, and large vendors that expressed interest never committed deeply enough to change the trajectory.

CONCLUSION

Wave may not exist anymore, but it never really disappeared. It lives as a ghost inside the apps we use every day. When you watch someone’s cursor dance in Google Docs, that is Wave. When you embed a widget in Notion, that is Wave. When Figma lets ten designers work inside the same frame, that is Wave. Its spirit fractured and drifted into everything that came after.

The product died. The idea survived.

And maybe that’s half a better legacy than success.

Imagine opening one window that replaces your inbox, your chat, your shared documents, your project channels, and even your little side apps like polls or maps. Imagine typing a word and everyone watching it appear letter by letter. Imagine dragging a file into a conversation and the file instantly becoming part of the shared document. Imagine replying inside someone’s paragraph as if the entire conversation were clay you could reshape at any moment. All of this happening in real time across browsers, devices, servers, continents back in 2009.

That fever dream was Google Wave.

Long before Notion, Slack or any collaborative tools existed, Wave was out there to solve a problem that was way ahead of its time. Every conversation was a document of its own and every document was a space where humans and bots could collaborate in real time. Wave treated messaging as a constantly evolving chain of inferences. Work happened inside a conversation instead of around it. The architecture backed this vision with serious engineering muscle: real-time merging, multi-server federation, event-stream persistence, client-side optimistic updates, and a universal representation for everything from text to files to bots. It was ambitious, it was bold, and it was genuinely ahead of its time. But ambition had a price and Wave paid all of it all at once.

The Master Architecture

When you typed even a single letter, your browser didn’t upload a paragraph or send a diff. Instead, it sent a tiny instruction like: Insert ‘a’ at position 142, based on version 389.

If someone else typed in the same region before you, the server adjusted the position. It updated its authoritative version. It appended the event to the log. And then it broadcast the smallest possible update to everyone else. Today if you build a collaboration tool your architecture would simply look something like this :

1. Put files on S3

2. Put docs in Postgres/ Firestore

3. Use Redis for updates

4. Stream live changes with WebSockets

5.Scale with serverless

Wave did not have these luxuries. Instead it used Google’s internal distributed systems to store :

1. Snapshots - periodic full versions of the entire wave

2. Event logs - tiny changes being changed forever

Even a file was inserted as a file object pointer. Wave did not have the privilege of throwing in Redis streams / CRDT libraries so it build its own pipeline. Every change was compared to the client version to server version, adjusted according to the edit so that it lands correctly and the master copy is updated. The newer version was incremented and the updates were broadcasted to all connected browsers. This was happening dozens of times per second, in a world where most web apps were still doing full page reloads.

One of Wave’s wildest architectural ideas was that different organizations could host their own servers, yet still participate in the same wave. Imagine if a Slack channel could be shared across two companies without both sides being on Slack’s cloud. Modern tools don’t do this. Wave did. If you added someone from other domain :

1. Your server sent their server the snapshot.

2. All future micro events were forwarded

3. Both servers maintained their own copies, always in sync.

4. Both servers broadcast updates to their own respective users.

Distributed event logs before Kafka, bots before LLMs became a thing, real time editing before Figma was even born - Wave wasn't just early - they were running on an architecture no one had. It was a Formula 1 car if introduced in the 1900s.

One Shot

a live shared document streamed through tiny updates, backed by a versioned event log, merged by an always authoritative server, synchronized across multiple domains, and built before the internet had the infrastructure to support such a thing.

Weak Onboarding and Complexity

Wave repeated Gmail’s invite-only rollout but with completely different stakes. Gmail worked fine under an invite model because users already knew what email was and could use it immediately even with just one contact. Wave, in contrast, was unfamiliar, required a group of people to see value together, and depended on network effects to demonstrate its potential. By limiting invites and spreading them slowly, Google prevented users from onboarding their actual work groups, so people tested Wave with a handful of friends for a few days and quickly abandoned it.

Consumer behavior in 2009 did not align with what Wave required. People were deeply entrenched in email, instant messaging, SMS, and growing social networks. Enterprises had begun adopting SharePoint, internal wikis, and early collaboration platforms. Wave’s benefits were real but subtle, and they did not obviously outweigh the effort required to switch.

Confusion about purpose & value

Wave never answered the simplest product question: what problem does this solve better than the tools people already use.

Some people approached it expecting a better email client, others thought it was a new type of chat, others assumed it was a document editor, while the Wave team’s own messaging often described it as a platform rather than an app. This ambiguity made it nearly impossible for new users to understand why they should adopt it or what everyday habit it was supposed to replace.

Many reviewers called it “too ambitious,” “too complicated,” or simply “too much,” noting that instead of reducing friction, Wave often increased cognitive load by presenting far more information and activity than users could comfortably track. Even experienced early adopters often needed long explanations just to understand how to reply, where edits were happening, or how to control the flow of conversation. When a product requires effort just to understand the basics, mainstream adoption becomes extremely unlikely.

Even though Wave offered robots, gadgets, and the promise of becoming a programmable collaboration platform, the ecosystem never reached meaningful scale. The extensions that existed were mostly prototypes or novelty features, and large vendors that expressed interest never committed deeply enough to change the trajectory.

CONCLUSION

Wave may not exist anymore, but it never really disappeared. It lives as a ghost inside the apps we use every day. When you watch someone’s cursor dance in Google Docs, that is Wave. When you embed a widget in Notion, that is Wave. When Figma lets ten designers work inside the same frame, that is Wave. Its spirit fractured and drifted into everything that came after.

The product died. The idea survived.

And maybe that’s half a better legacy than success.

Imagine opening one window that replaces your inbox, your chat, your shared documents, your project channels, and even your little side apps like polls or maps. Imagine typing a word and everyone watching it appear letter by letter. Imagine dragging a file into a conversation and the file instantly becoming part of the shared document. Imagine replying inside someone’s paragraph as if the entire conversation were clay you could reshape at any moment. All of this happening in real time across browsers, devices, servers, continents back in 2009.

That fever dream was Google Wave.

Long before Notion, Slack or any collaborative tools existed, Wave was out there to solve a problem that was way ahead of its time. Every conversation was a document of its own and every document was a space where humans and bots could collaborate in real time. Wave treated messaging as a constantly evolving chain of inferences. Work happened inside a conversation instead of around it. The architecture backed this vision with serious engineering muscle: real-time merging, multi-server federation, event-stream persistence, client-side optimistic updates, and a universal representation for everything from text to files to bots. It was ambitious, it was bold, and it was genuinely ahead of its time. But ambition had a price and Wave paid all of it all at once.

The Master Architecture

When you typed even a single letter, your browser didn’t upload a paragraph or send a diff. Instead, it sent a tiny instruction like: Insert ‘a’ at position 142, based on version 389.

If someone else typed in the same region before you, the server adjusted the position. It updated its authoritative version. It appended the event to the log. And then it broadcast the smallest possible update to everyone else. Today if you build a collaboration tool your architecture would simply look something like this :

1. Put files on S3

2. Put docs in Postgres/ Firestore

3. Use Redis for updates

4. Stream live changes with WebSockets

5.Scale with serverless

Wave did not have these luxuries. Instead it used Google’s internal distributed systems to store :

1. Snapshots - periodic full versions of the entire wave

2. Event logs - tiny changes being changed forever

Even a file was inserted as a file object pointer. Wave did not have the privilege of throwing in Redis streams / CRDT libraries so it build its own pipeline. Every change was compared to the client version to server version, adjusted according to the edit so that it lands correctly and the master copy is updated. The newer version was incremented and the updates were broadcasted to all connected browsers. This was happening dozens of times per second, in a world where most web apps were still doing full page reloads.

One of Wave’s wildest architectural ideas was that different organizations could host their own servers, yet still participate in the same wave. Imagine if a Slack channel could be shared across two companies without both sides being on Slack’s cloud. Modern tools don’t do this. Wave did. If you added someone from other domain :

1. Your server sent their server the snapshot.

2. All future micro events were forwarded

3. Both servers maintained their own copies, always in sync.

4. Both servers broadcast updates to their own respective users.

Distributed event logs before Kafka, bots before LLMs became a thing, real time editing before Figma was even born - Wave wasn't just early - they were running on an architecture no one had. It was a Formula 1 car if introduced in the 1900s.

One Shot

a live shared document streamed through tiny updates, backed by a versioned event log, merged by an always authoritative server, synchronized across multiple domains, and built before the internet had the infrastructure to support such a thing.

Weak Onboarding and Complexity

Wave repeated Gmail’s invite-only rollout but with completely different stakes. Gmail worked fine under an invite model because users already knew what email was and could use it immediately even with just one contact. Wave, in contrast, was unfamiliar, required a group of people to see value together, and depended on network effects to demonstrate its potential. By limiting invites and spreading them slowly, Google prevented users from onboarding their actual work groups, so people tested Wave with a handful of friends for a few days and quickly abandoned it.

Consumer behavior in 2009 did not align with what Wave required. People were deeply entrenched in email, instant messaging, SMS, and growing social networks. Enterprises had begun adopting SharePoint, internal wikis, and early collaboration platforms. Wave’s benefits were real but subtle, and they did not obviously outweigh the effort required to switch.

Confusion about purpose & value

Wave never answered the simplest product question: what problem does this solve better than the tools people already use.

Some people approached it expecting a better email client, others thought it was a new type of chat, others assumed it was a document editor, while the Wave team’s own messaging often described it as a platform rather than an app. This ambiguity made it nearly impossible for new users to understand why they should adopt it or what everyday habit it was supposed to replace.

Many reviewers called it “too ambitious,” “too complicated,” or simply “too much,” noting that instead of reducing friction, Wave often increased cognitive load by presenting far more information and activity than users could comfortably track. Even experienced early adopters often needed long explanations just to understand how to reply, where edits were happening, or how to control the flow of conversation. When a product requires effort just to understand the basics, mainstream adoption becomes extremely unlikely.

Even though Wave offered robots, gadgets, and the promise of becoming a programmable collaboration platform, the ecosystem never reached meaningful scale. The extensions that existed were mostly prototypes or novelty features, and large vendors that expressed interest never committed deeply enough to change the trajectory.

CONCLUSION

Wave may not exist anymore, but it never really disappeared. It lives as a ghost inside the apps we use every day. When you watch someone’s cursor dance in Google Docs, that is Wave. When you embed a widget in Notion, that is Wave. When Figma lets ten designers work inside the same frame, that is Wave. Its spirit fractured and drifted into everything that came after.

The product died. The idea survived.

And maybe that’s half a better legacy than success.

Be the first to know about every new letter.

No spam, unsubscribe anytime.